2025 has been the year agentic AI moved from hype to reality. Since January, HUMAN has measured a 6,900 percent increase in AI-agent traffic and a meaningful rise in commerce-related agent actions across the web.

These are exciting times, but for security teams, it’s a bit like waiting for the other shoe to drop.

AI agents can chain actions, navigate authenticated sessions, and execute multi-step tasks with speed and consistency. In the hands of a threat actor, those capabilities remove much of the friction that traditionally constrained automation-driven attacks.

So how long before the same tools that power legitimate automation start appearing in fraud and abuse workflows?

In November, Anthropic released research indicating that adversaries are already trying to weaponize AI systems. Their researchers disrupted a state-aligned espionage attempt involving the manipulation of Claude Code into generating malicious scripts, analyzing target networks, and preparing intrusion steps against roughly thirty organizations. That is scary, but it’s not what most organizations are bracing for. Espionage against high-value targets is fundamentally different from the broad, repetitive, monetization-driven abuse that defines day-to-day cybercrime.

As agent adoption accelerates, we are beginning to see early signs of attackers testing AI agents inside far more routine fraud and abuse workflows.

In this Satori perspective, we’ll break down a recent example of potential carding abuse involving an unusual credit-card-related sequence conducted through an AI agent. The pattern closely resembled early-stage carding behavior: rapid card additions, repeated payment attempts, and a fallback to loyalty-point redemption once all card paths failed.

What we observed: A real-world carding-like pattern from an AI browser

Among the billions of agent interactions HUMAN analyzes each day, this event sequence stood out for how closely it mapped to early-stage carding behavior. While this is one example, it is not an isolated signal. It reflects the kind of experimentation we are beginning to see as attackers probe how AI agents behave inside real payment flows.

What happened

Over two days, an AI agent we identified as an instance of Perplexity Comet browser initiated two purchase attempts on a retail account. Across both sessions, the agent triggered six total payment-completion attempts and attempted to add eleven different credit cards to the account. This pattern aligns with “checking,” a common carding technique wherein attackers iterate through multiple cards to identify one that will authorize successfully.

The sequence proceeded in three phases:

Figure 1 illustrates the progression across the two days: two purchase attempts, six payment-completion attempts, eleven card-additions, and a final successful transaction via loyalty-point redemption.

A purchase attempt in this case is the identifier for the user’s cart, all shipment information, payment details, and discounts. A payment completion attempt is each session where the agent attempts to finalize the payment in order to receive a payment confirmation. As part of the first purchase attempt, we see five failed payment completion attempts, including one in which the agent attempts to use the pinned credit card and another in which it attempts to redeem the account’s loyalty points. In the second purchase attempt, we see the agent successfully complete the purchase using the account’s loyalty points.

While the total volume here is not large, the structure of the activity matters. The rapid card-addition loop, short-interval retries, and immediate pivot to a secondary payment instrument all align with established carding patterns. Except in this case, the behavior was mediated by an AI agent. It is an early marker of how agents may be incorporated into real-world fraud attempts as attackers test the boundaries of agentic automation.

Why AI agents are appealing tools for account abuse

The carding-like sequence we observed is only one example of how attackers may begin to use AI agents inside compromised accounts. Once a threat actor gains access to a victim’s account, an agent becomes a powerful automation layer: it can iterate quickly, perform multi-step tasks, and carry out actions that normally require the user to be present. This is why account abuse is a likely early frontier for malicious agent usage.

Several characteristics make agents particularly attractive tools for this kind of activity:

Faster iteration than manual attackers

Agents can retry flows, like adding cards, submitting forms, or toggling between payment methods, at a speed and consistency that human attackers cannot match. The compressed timing patterns we saw in the observed sequence show how an agent can rapidly cycle through failure states that a human would space out over minutes or hours.

Blended human and automated behavior

Unlike a bot, an agent’s activity can be partly user-driven and partly autonomously executed. This blend makes detection harder. A threat actor can prompt an agent to “fix the payment issue,” and the agent will carry out a sequence of steps that, in aggregate, look like a fraud workflow but individually resemble normal user actions.

Ability to operate inside authenticated sessions

Once an attacker controls an account, an agent can be instructed to perform downstream actions that require authentication: editing personal information, changing credentials, draining stored value, or manipulating payment settings. If the website implicitly trusts actions from known agents, the risk compounds.

Ability to chain actions programmatically

Agents do not simply click buttons. They interpret instructions, inspect on-page context, update internal plans, and revise their next action. This means abuse is not limited to single-step automations; it becomes a sequence of interdependent steps that resemble how a human would navigate, but executed with machine efficiency.

What does this mean for account security?

Carding is not the only threat. Once inside an account, an attacker could use an agent to:

Any action that a human user can take inside an authenticated session is, in principle, available to an agent unless explicitly restricted.

This is why relying only on “agent authenticity,” i.e. verifying that the traffic really came from a known agentic browser, is insufficient. A verified agent can still be misused. The critical question is not only who the agent is, but what the agent is being allowed to do.

Context Is Essential

Evaluating agent actions in isolation offers very little security value. A single password-change attempt looks harmless unless it is preceded by dozens of login retries. A loyalty redemption is benign unless it follows a cascade of failed credit-card checks. Without visibility into the chain of actions, organizations cannot distinguish legitimate agent-assisted shopping from early-stage abuse.

Context-aware controls allow businesses to define boundaries:

This is the model that will allow retailers to benefit from agentic commerce without exposing themselves or their customers to unnecessary risk.

Looking Forward: The Agentic Internet

We’re facing a new class of adversaries and a new class of allies at the same time. Success in the agentic era will depend on the ability to verify and trust automated agents, not simply block them.

As this ecosystem continues to evolve, organizations that thrive will move beyond simple blocking strategies to embrace sophisticated governance approaches that can adapt to the nuanced reality of AI-powered interactions.

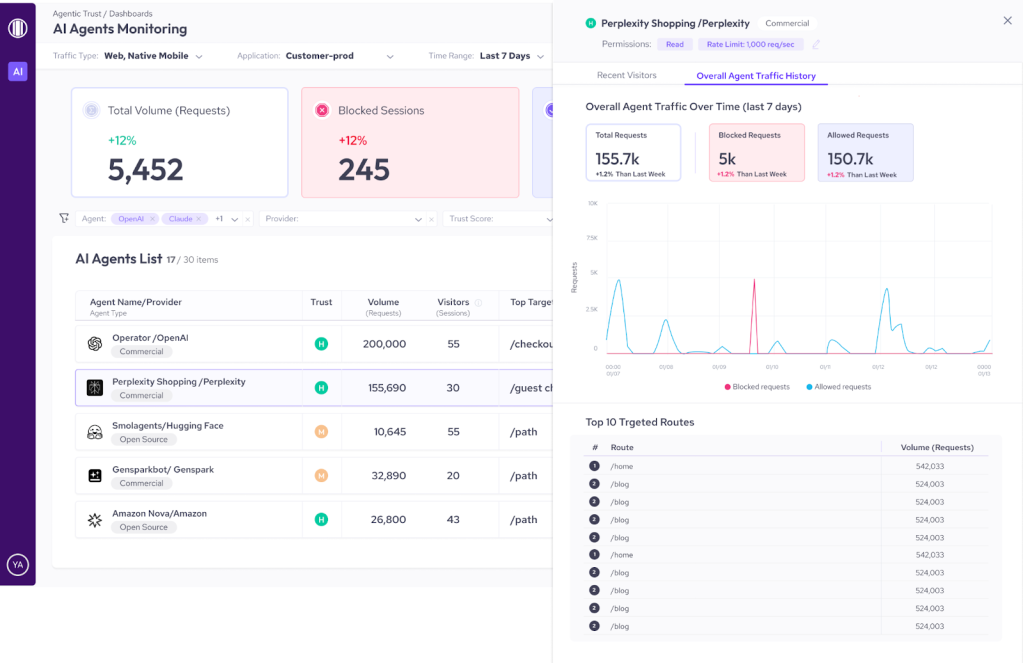

That’s why we built AgenticTrust, a new module in HUMAN Sightline Cyberfraud Defense, built to give you visibility, control, and adaptive governance over agent-based activity in your websites, applications, and mobile apps.

See how AI agents touch your app, review permissions and rate limits, visualize traffic over time, and identify the most targeted routes.

AgenticTrust gives security and fraud teams continuous visibility into the AI agents interacting with their websites and applications. It identifies agents, classifies their behavior, and enforces rules that govern what agents are allowed to do and what they’re not, so you can allow agentic commerce responsibly.

Ready to govern AI agents, scrapers, and automated traffic with precision and confidence? Discover how AgenticTrust provides the visibility, control, and adaptive governance you need to safely enable agentic commerce while protecting against abuse across your entire customer journey. Request a demo today.