Researchers: Louisa Abel, Philipp Blenke (The Trade Desk), Maor Elizen, Francis Kitrick, Will Herbig, Peter Macias, Vikas Parthasarathy, João Santos, Adam Sell, Braedon Vickers

IVT Taxonomy: False Representation: App Spoofing, False Representation: Spoofed Measurement

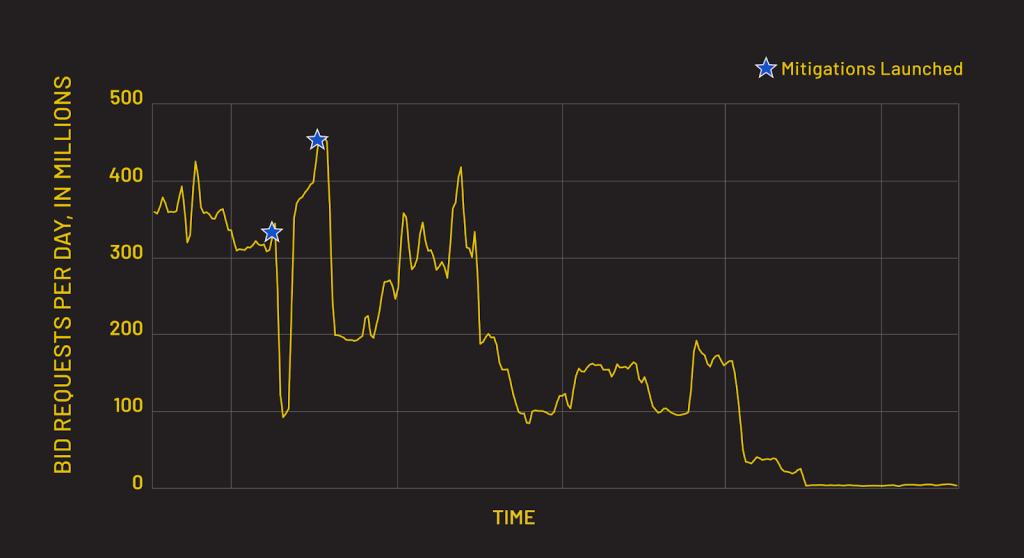

HUMAN’s Satori Threat Intelligence and Research Team, in partnership with The Trade Desk, has uncovered and disrupted an ad fraud operation dubbed Apollo. This scheme centered on spoofed bid requests, taking advantage of lower visibility on server-side ad insertion (SSAI) traffic commonly used in the audio advertising marketplace. At its peak, Apollo accounted for 400 million fraudulent bid requests a day, the highest peak volume of audio-related ad fraud ever uncovered. Indeed, fraudulent bid requests associated with Apollo reached 10% of all audio bid requests observed by the Human Defense Platform.

Apollo, so named for the Greek god’s association with music, is chiefly defined by fabricated audio requests. Many of these requests claimed to be from apps for which audio ads are unlikely or impossible. Apollo is reflective of the challenges the industry continues to face with respect to server-side ad insertion (SSAI), the technology used to deliver many audio ads.

Apollo represents not just a novel audio operation, but a deeper view into how threat actors are working together to evade detection. HUMAN observed Apollo-associated traffic funneled through the residential proxy capabilities enabled by the BADBOX 2.0 infection. (BADBOX 2.0 was the largest botnet of infected CTV devices ever uncovered, and controlled more than one million devices.) One such device in HUMAN’s Satori lab passed hundreds of Apollo-associated bid requests in the span of just a few hours, all using the residential IP address of an infected device to hide the originating IP address.

Customers partnering with HUMAN for ad fraud defense are heavily protected from the impact of Apollo.

“Ad Fraud can only be effectively prevented through collective protection and close industry collaboration. To build a more secure and transparent digital ecosystem, it is essential to enhance threat-sharing initiatives and accelerate the development of robust, enforceable transparency standards.”

– Philipp Blenke, Director of Marketplace Quality, The Trade Desk

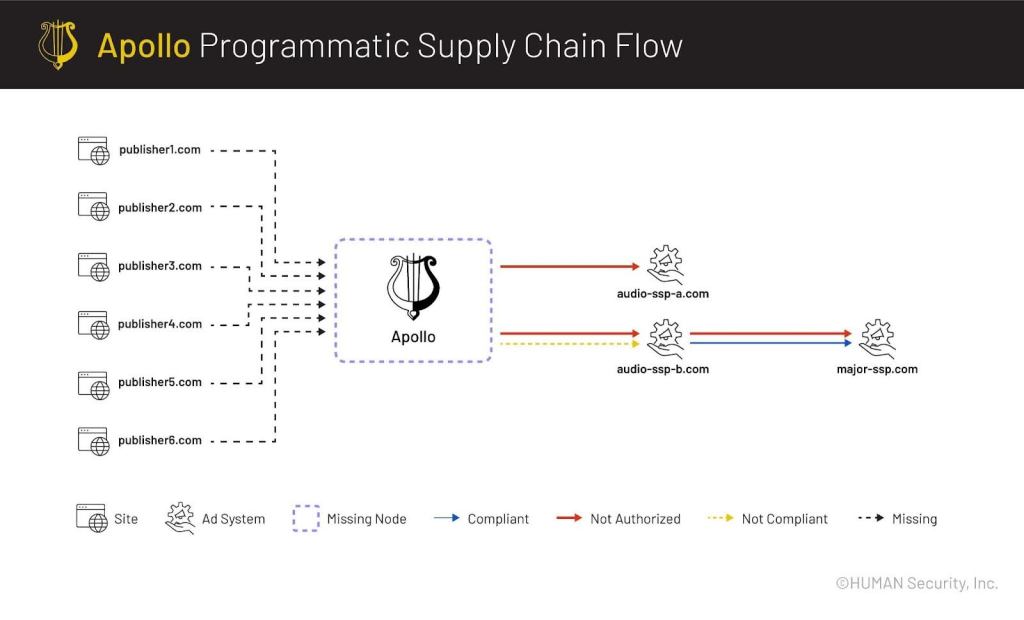

The Apollo story also reflects a weakness in a common implementation of supply chain enforcement: much of the Apollo-associated traffic is app-ads.txt verified on the last seller, so it appears as though it is authorized traffic. One must validate each and every step of the supply path to identify that the originating seller is claiming to sell traffic on apps they own, but they do not appear related to those apps. This reinforces the need for greater scrutiny and enforcement on app-ads.txt across the industry. HUMAN’s compliance dashboard provides customers visibility into end-to-end supply chain authorization.

Background: SSAI and Spoofing

Much like Connected TV (CTV) advertising before it, audio ads are highly valued in the digital advertising ecosystem. And also like CTV advertising, there’s limited signal and transparency in server side ad insertion (SSAI) backed audio ad impressions. This combination is enormously attractive to threat actors.

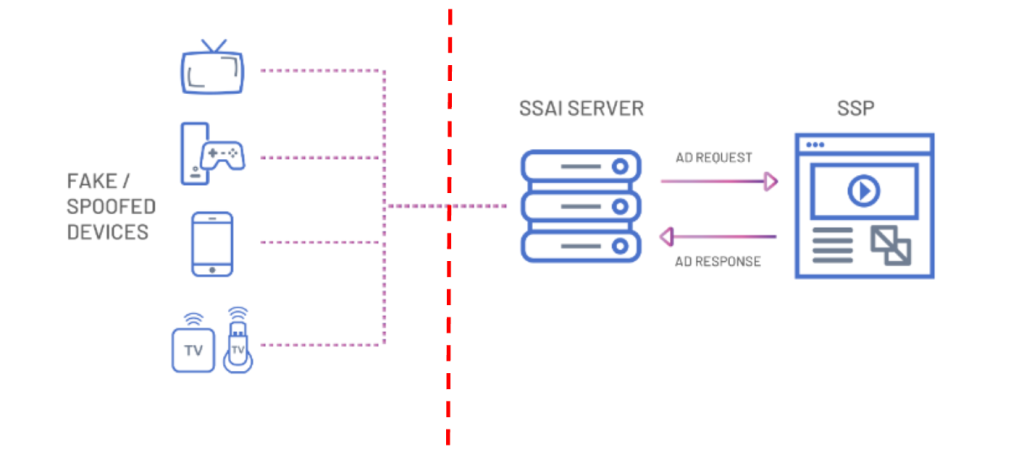

The Apollo threat is best understood within the context of server-side ad insertion (SSAI) and how threat actors spoof impressions in ecosystems that rely on this ad delivery technology.

In our ICEBUCKET investigation in 2020, we wrote:

Server-side ad insertion, or SSAI, was developed by publishers to create a better end-user ad experience. Ads are “stitched” into the fabric of streaming content so that there aren’t delays or hiccups caused by launching an ad player. SSAI is commonly used for advertising on several device types, such as CTVs, smart phones, gaming consoles, and others. Delivering streaming ad content through SSAI offers advertisers many benefits, including user personalization and latency reduction.

SSAI spoofing occurs when fraudsters send out a bunch of ad requests from data centers for “spoofed” or faked edge devices. The data center source is expected for real SSAI providers. Rather than show the ads to humans, the fraudsters call the reporting APIs indicating the ad has been “shown”. Often, the information available to advertisers in an SSAI environment is limited to the device user-agent and IP address. This information may be sent in the “X-Device-User-Agent” and “X-Device-IP” HTTP headers, as per the IAB VAST guidelines, or through other similar headers. While falsifying this data is relatively simple, the nuance of doing so convincingly makes this a form of a sophisticated bot attack.

SSAI is a common delivery mechanism for audio content, and in the five years since the ICEBUCKET report the industry hasn’t fully resolved the challenges with SSAI fraud.

Spoofed bid requests are bid requests that contain partially or entirely incorrect attribute declarations. An entire bid request can be generated artificially and sent into the supply chain, but not represent a genuine request (i.e., the request doesn’t convert to an impression as described in the bid request).

For example, a bid request may declare the app ID as one app, but load the impression on another app, a threat vector known as mobile app spoofing. Devices, too, can be impersonated or spoofed, with the ad loading on a virtual machine, data center, or different device.

App and device spoofing techniques were both observed on Apollo.

Technical Analysis: What We Saw

Apollo traffic was found mostly in mobile web and mobile in-app contexts, but a subset of traffic was observed with declared configurations more typically associated with audio, such as podcast apps, radio apps, and even some smart speakers.

Satori researchers observed Apollo-related bid requests claiming to be from app IDs that showed evidence of spoofing or material misrepresentation. The reported device configurations for the fraudulent bid requests had little to no overlap with the device configurations found in the organic, genuine traffic observed from other supply sources transacting on that app. Further, the Open Measurement SDK (“OMSDK”), which was designed to facilitate third party verification measurement for ads especially in the context of mobile advertising, was never present in Apollo traffic.

Notably, some bid requests claimed to represent ads on apps that aren’t expected to serve audio ads; the only times we saw audio ads coming from these apps was on supply paths associated with Apollo. For example, it’s intuitive to see audio ads within music streaming and radio apps, but it’s much less common to find audio ads on a puzzle or weather app (which would more typically serve display or video ads).

HUMAN’s comprehensive detection measures against Apollo have resulted in traffic associated with the scheme dropping significantly more than 99% from its peak volume. Customers partnering with HUMAN for Ad Fraud Defense were heavily protected from Apollo.

Behind the Bid Request: Generating Spoofed Traffic

During our recent investigation into BADBOX 2.0, we observed Apollo bid requests flowing through one of the BADBOX 2.0-infected devices in the Satori lab. The requests were funneled through the residential proxy network facilitated by the BADBOX 2.0 infection. This unusually lucky occurrence gives a rare “behind-the-scenes” example into one path threat actors take to spoof requests. Residential proxy services help threat actors hide malicious behavior by making it seem as though requests come from diverse residential IPs, rather than from the actual devices on which the behavior originated. This incident also strongly reinforces the value to the digital advertising ecosystem of collective protection and proactive threat research.

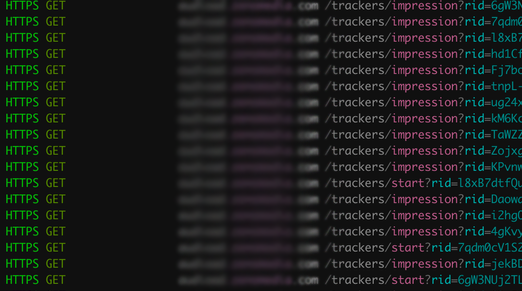

On the infected device, researchers saw hundreds of Apollo requests generated in sequence with randomized user agents in the span of a few hours’ observation. These requests were preceded by an IP check using third-party services, suggesting the threat actors were testing the residential proxy connection and confirming the IP address before sending the fraudulent requests.

Each bid request claimed to be for one audio content monetization and distribution company, and had been custom-generated to mimic legitimate bid requests from that specific audio publisher.

Our researchers observed that the threat actors copied the exact impression request flow from the publisher’s legitimate app, meaning they had specifically and intentionally copied the bid request format for the publisher to hide their invalid traffic among legitimate traffic. The traffic researchers observed was likely generated by a script, which allowed the threat actor to generate and modify requests in bulk, with whatever parameters they wanted.

Based on the evidence gathered by our researchers, this was the likely process for generating these bid requests:

- Grab the direct feed URL of an audio stream or audio app they want to copy

- Capture the traffic or reverse engineer the app to get the streaming URL

- Create a script to automatically generate activity resulting in impression requests for the ads

Apollo & SupplyChain Object Compliance

HUMAN identified a number of standards compliance issues in the supply chains of Apollo traffic.

First, it is important to note that for a significant proportion of this inventory, the last seller in the SupplyChain object was an intermediary that was app-ads.txt authorized. If the buyer only checks whether the final seller is authorized—rather than the whole supply chain—then the spoofed inventory will appear to be authorized by the publisher.

HUMAN observed that specific sellers were claiming to be the publisher of these apps (i.e., using PUBLISHER seller accounts they own as the first node in the SupplyChain objects). However, there’s no evidence these sellers own these apps, so the SupplyChain objects fail standards compliance checks. Further, the specific seller accounts aren’t authorized by the apps at all. At a minimum, this is poor adherence to industry standards, and at worst, it reinforces the conclusion of mobile app spoofing.

This may be a case of “supply chain convergence”. Because many sites and apps authorize large numbers of reseller accounts, if a threat actor can get unauthorized spoofed inventory into the programmatic ecosystem, it’ll likely eventually find its way through intermediaries to a reseller account that happens to be authorized by the publisher being spoofed – the unauthorized inventory’s supply chain “converges” with a legitimate supply chain the publisher was trying to authorize.

How HUMAN Protects from Audio Threats

HUMAN has deployed numerous proprietary detection techniques against Apollo and other audio threats.

Additionally, the compliance dashboard within MediaGuard, HUMAN’s Ad Fraud Defense solution, gives customers the ability to see full end-to-end supply path compliance checks and many SupplyChain completeness metrics to give transparency to customers on where their inventory might have discrepancies.

HUMAN Researchers expect schemes centering on audio fraud to continue to grow in scale and complexity. Solving the challenge of audio fraud prevention requires an industry-wide approach.

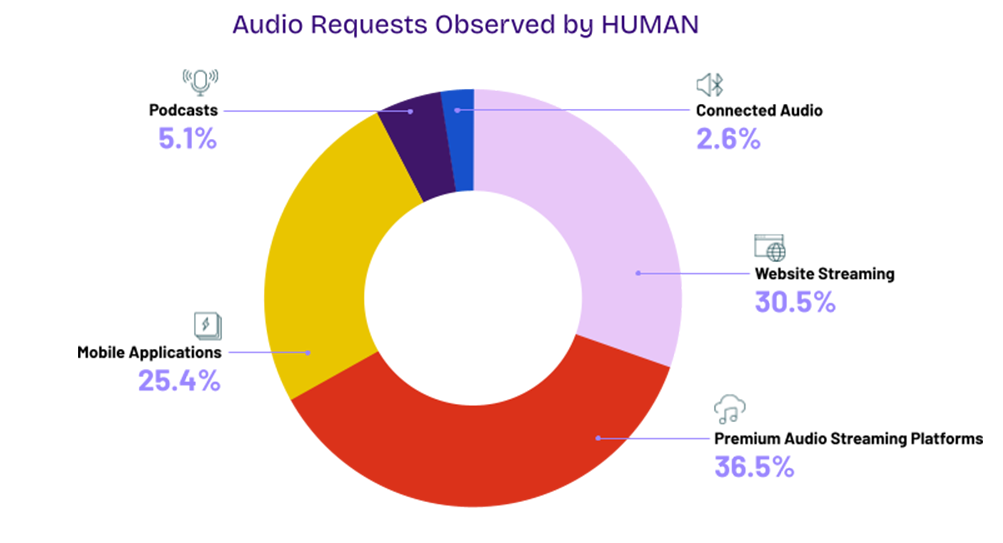

The Human Defense Platform observes audio bid requests across a wide variety of channels:

HUMAN believes the best way to mitigate IVT in audio is through collective protection and industry-wide collaboration. The industry taking action such as creating a standardized audio taxonomy, improving the frequency of full end-to-end SupplyChain compliance checks, and further adoption of third party measurement like the Open Measurement SDK will collectively improve the coverage of SIVT on Audio inventory.

Conclusion

As demand for audio content grows—eMarketer projects programmatic audio advertising spending to cross $2 billion in 2025 with continued growth into 2026 and beyond—it is critical the programmatic ecosystem increase their vigilance on monitoring audio for IVT schemes. While HUMAN’s researchers combat audio fraud with the tools available today, continued collaboration and knowledge-sharing through working groups like the Human Collective and partnerships like HUMAN’s with The Trade Desk will also enable faster discovery and faster dismantling of schemes like Apollo.

While HUMAN customers are protected, this is a prime example of inventory spoofing operations that many advertising stakeholders can protect themselves from by conducting full end-to-end supply chain compliance checks. HUMAN’s customers can easily access their compliance dashboard which flags supply chain compliance issues and empowers corrective action.